Fixed income, rates & currency: US debt crisis averted – what next?

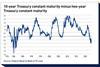

The US debt ceiling crisis was resolved in June, avoiding potentially major fireworks, with a suspension of the limit until early 2025. This ensures that the next time the politicians have to fight about it will be after the November 2024 presidential election. Although markets were relieved at the temporary resolution, the process of rebuilding the very depleted Treasury cash balances – with some huge bill auctions planned – will drain significant liquidity from the system, which could put pressure on the rates market.

This content is only available to IPE Members

Already an IPE Member? Sign in here

Unlock your IPE Membership Package

For unlimited access to IPE’s industry-leading market intelligence, comprising news, data and long-form content on European pensions and institutional investment.

- Secure online payment

- Free European delivery

IPE Membership

IPE has created a suite of products and services for Europe’s institutional investment and pensions community.

country analysis and data

and strategies in depth