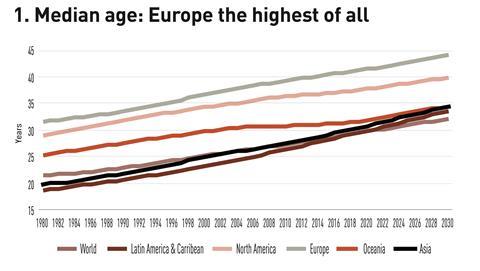

The continent is the oldest in the world, with fast shrinking populations and lower fertility rates

Key points

- The challenge of fewer younger people places potential strains on growth, debt and stability, and threatens living standards

- While Europe as a whole is ageing, policymakers will have to take heed of the differences between individual countries

- Changing consumer behaviour, work patterns and technology use, led by the younger generations, could improve conditions for all

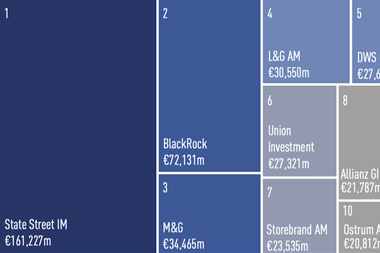

When it comes to demographics in relation to European growth and fiscal sustainability, an important factor for policy-makers to consider is the significant heterogeneity across the 27 European Union countries. In a report shortly after the global financial crisis on ageing countries, we showed that four of the five oldest countries were in Europe. In this article, my focus is on the largest EU countries exemplifying these differences: France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain and Sweden.

Policy-makers will be able to enact and implement effective policies underlying a growing and sustainable EU only if they face up to the underlying heterogeneity across member states. Progress has been slow despite good objectives and policy research from the European Commission in its Ageing and Fiscal Sustainability reports.

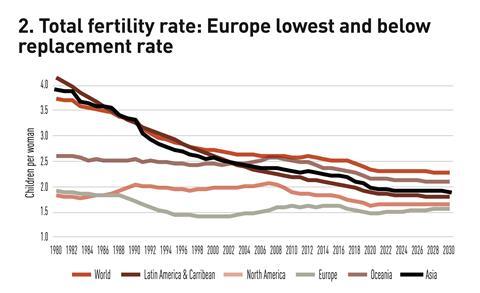

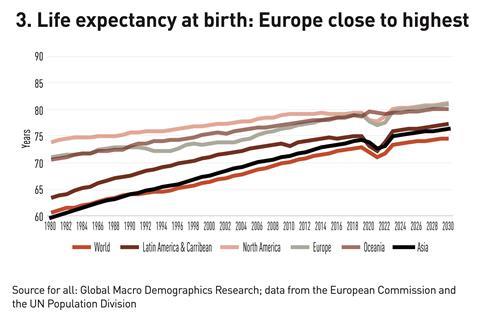

Europe is the oldest region in the world, and is shrinking fastest in numbers and fertility rates (see figures).

This means Europe is the ageing leader and probably the wise old person in the world. But that comes with challenges of fewer younger people and places potential strains on growth, debt and stability. It also poses a threat to the living standards of current and new generations. Low fertility rates (children per woman) and higher life expectancy also lead to high old-age dependency ratios – where a larger share of old people needs to be supported by a smaller share of young people. Europe’s fertility rate of 1.5 children per woman is far below the replacement rate of 2.1.

This explains the lower share of young people in next few years relative to other regions. The life expectancy at birth is higher for Europe but not that much higher than North America and Oceania. A similar trend is seen for life expectancy at older ages.

These trends are not uniformly very close across the six largest European economies.

Sweden had one of the highest median ages and life expectancy in the 1980s but while its life expectancy at birth has not changed much, its median age now is the lowest. This is explained by the high (relative to population) immigration into Sweden in the 1990s of younger immigrants. The increased immigration correlates with higher fertility rates and higher population change rates as well as higher crude rates of net migration. Therefore, we are using Sweden’s changing demographics to illustrate the impact of immigration trends on life expectancy, fertility and population change rates across Europe. These contribute to explaining the differences between countries.

“The ageing population leads to higher public debt to deal with pensions, healthcare and

long-term care”Amlan Roy

Immigration practice differs significantly across Germany, France and Italy in terms of integration costs and when immigrants start contributing positively net of the costs, with Germany benefitting from immigration in the 1990s. Spain, too, saw significant net migration in the early 2000s.

The composition of national and club football teams is a good illustration of the changing composition of people in the nation. France, US and UK have a sizeable contribution of population change coming from net migration. The change in population is measured by adding net migration numbers to births and deducting deaths.

During the COVID pandemic, immigration suffered across all countries as travel restrictions were imposed and this had an adverse impact on GDP growth across the world and in particular for countries that rely on foreign labour for production of goods and services.

Living longer, work longer

The changing demographics have implications for growth, debt and fiscal stability. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has since the start of the millennium advocated a policy of ‘Live Longer, Work Longer’ as part of managing debt sustainability, growth and stability. However, as recent strikes and unrest in France show, it is hard to convince people to work longer, even if it is for the collective good as well as in their own self-interest. Progressive smaller countries are finding it easier to link retirement ages to changing longevity (life expectancy).

Demographics affect GDP growth, public debt to GDP as well as living standards. The European Commission has highlighted the impact of ageing in its ageing and fiscal sustainability reports which analyse the past, current and the future based on projections and scenarios. Since 2009, I have argued for holistic policy reform across labour, education, health and pension policies to deal with the adverse effects of ageing on productivity, growth and living standards. In ‘The Demographic Manifesto’ we advocated a radical combination of four policies to tackle the ageing timebomb: flexible retirement with no fixed ages; better female labour force engagement and utilisation; selective immigration based on existing skills; and outsourcing/offshoring. Technology should underpin all four pillars to combat ageing.

Shrinking populations translate to lower future working age population levels; ageing populations lead to lower productivity levels, which is further impacted by labour legislation capping the hours worked per week in many countries. These features combine to lower GDP growth. The ageing population also leads to higher public debt to deal with pensions, healthcare and long-term care of the older, inactive population. The cost of pensions, healthcare and long-term care is projected to rise from 22% of GDP to about 25-26% under current policy norms. We are all aware of the growth-limiting prospects created by debt, especially in an environment of rising interest rates.

If populations decline and GDP grows, then GDP per capita could increase. The growth of GDP relative to the growth rate of population is therefore very important. The older population of baby-boomers born during or just after the second world war benefitted greatly from the overall asset performance of the 1980s and 1990s, combined with high GDP growth in Europe. The younger generations are unlikely to be as rich.

We should pay serious attention to the projections by the European Commission and its economic affiliates over the 2019-70 period, which include:

- The old-age dependency ratio is projected to increase from 34% to 59%) due to rise in life expectancy by 7.4 years dominating the small increase in fertility rates from 1.52 to 1.65;

- Labour force participation especially of older workers will continue to increase yet labour supply will fall;

- Employment rates will increase but the number of employed will decrease;

- As labour growth decreases only increase in labour productivity growth can result in projected GDP growth of 1.6% between 2019 and 2070;

- the COVID fallout presents risk to future growth prospects;

- The total EU population is expected to shrink by 15.2m more than that projected in 2018, which will lead to a higher old age dependency ratio of 1.7% in 2070

- The GDP of the EU27 is projected to grow 1.3% from 2019 to 2070, while GDP per capita is estimated to grow 1.4% if the population continues to shrink.

Changing consumer behaviour

Ageing also contributes to financial stability risks because of questions over debt sustainability and income distribution. Policy changes are therefore needed to create the right conditions for a high-growth, low-debt and stable economy. Holistic reforms in labour, health, education, technology and debt are required. However, as the case of France shows, resistance to changes in retirement, immigration and labour practices originates from the older workers who are beneficiaries of promised entitlements. Older voters participate in elections in greater numbers than younger ones, and therefore politicians tend to cater to their interests. Greater inequality across regions, cities and generations can sow the seeds of discontent and revolt among disadvantaged members of society.

A possible silver lining to Europe’s ageing problem could be changing consumer behaviour, work patterns and technology adoption by the younger generations who may capitalise on the digital changes brought by artificial intelligence, machine learning and big data. This may lead to better financial prospects, health and productive lives for the entire population.

This is the personal viewpoint of Amlan Roy, who is the author of Demographics Unravelled and founder of Global Macro Demographics Research. He is a research associate at the London School of Economics and an honorary fellow of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries. His views do not reflect those of any institution or affiliation

Websites

We are not responsible for the content of external sitesSpecial Report – Outlook: Europe and the world

Inflation may be losing momentum, thanks to vigorous central bank action, but with a recession on the horizon, it is hard to tell whether the next few months and years will see markets turn around and risk assets begin to perform again. For the time being, CIOs argue for selectivity ...

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Outlook – Europe and the world: Ageing Europe puts strain on growth