Securitisation in Europe should be a key financing tool for generating growth in the European economy.

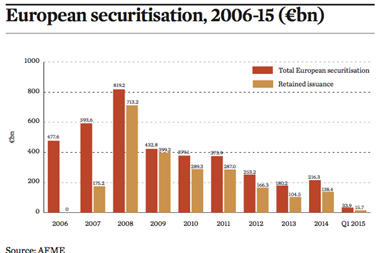

Unfortunately, the global financial crash in 2007-08 was induced by sub-prime losses in the US, which tarred securitisation across the globe. Regulators in Europe clamped down heavily on securitisation by imposing onerous capital and risk retention requirements. Total issuance shrank from €419.2bn in 2007 to €96.4bn in 2016, according to the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME).

Europe has always suffered from a less enthusiastic perception of asset-backed securities (ABS) compared to the US. As one ABS expert recounted, in the 1990s there was a strong feeling that it was an asset class that only institutions in trouble would utilise. The view was often that strong entities didn’t need such assets.

It appears that underlying sentiment remained in place throughout the growth of the market. When the crisis hit and the poster child for the disruption was the US sub-prime market, it was not difficult for those holding that view to tar the whole European ABS market with the same brush. This has been a major contributor to the punitive regulatory environment seen over the past decade.

Last week however, saw a major development that at least attempts to create a stimulus for European securitisation. The European Parliament, the Council and the Commission agreed on a package that set out criteria for “simple, transparent, and standardised securitisation” (STS).

The parties are hoping that a swift implementation of the securitisation package could unlock up to €150bn of additional funding for the real economy. The deal is seen as one of the cornerstones of the Capital Markets Union (CMU), the Juncker Commission’s pivotal project to build a single market for capital in the EU. The intention is to aid the transfer of risk from the banking sector, as securitisation enables banks to transfer the risk of some exposures to other institutions or long-term investors, such as insurance companies and asset managers. This would allow banks to free the capital they set aside to cover for risks of those exposures and hence allow them to generate new lending to households and small businesses.

The STS designation attempts to solve a key issue for institutional investors such as pension funds and insurance companies: how to differentiate the more questionable deals that may have complex risks hidden in them from the straightforward stuff? For the more questionable stuff, the capital charge should be punitive, but the problem is how do you differentiate? How do you define what is good? The STS designation provides that seal of approval.

As the EU Commission is keen to emphasise, the new legal framework bears no relation to the securitisation of sub-prime mortgages created in the US that contributed to the financial crisis. They are anxious to ensure that opaque and complex sub-prime instruments are not bought unwittingly by unsophisticated institutional investors.This (alongside a business strategy by financial firms of originating securitisations purely to distribute the whole product to third parties) was arguably a key factor in the global financial crash. By imposing high risk retentions on issuing banks together with a badge of comfort in the STS designation, regulators hope to avoid a repeat of the excesses seen in the US securitisation markets pre-2007.

European ABS participants have been frustrated by the slow progress in reopening these markets. European ABS never suffered from the losses seen in the US and, to that extent, market participants believe EU authorities have overreacted.

Global risk retention rules had suggested that sponsors/originators should retain a minimum of 5% risk exposure to align interests with investors. The European Parliament, however, had decided to increase this to 20% for all European deals. Such a figure would have dramatically reduced the efficiency of ABS as a funding tool relative to alternatives such as covered bonds.

It now looks as though agreement has been made to adhere to global standards, at least in this respect. However, the new regulations restrict participation in EU markets only to EU regulated financial institutions. That rules out US companies and also European corporates from securitising trade receivables.

More intriguing for the future may also be the question of how the EU’s securitisation markets will develop post Brexit, given that the UK has always had the largest ABS markets in Europe.