The Fed’s recent 25bps rate cuts came as investors were pondering weak US job data and the prospect of rising inflation

Though the announcements of new tariffs have become less frenetic in recent weeks, markets are still in a wait-and-see mode, pondering how much price pass-through costs will end up affecting consumer price indices. Following on from a burst of front-loading in the early months of the year, markets are waiting for more clarity on what companies – both exporters and US importers – and consumers are doing now the tariffs are largely in place.

Aside from ongoing debates regarding the accuracy or reliability of Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) surveys, the US jobs market is weakening, and rates were quick to already price in the Federal Reserve’s September policy rate cut of 25 basis points to a range of 4%-4.25%. Questions remain as to whether we are likely to see further rate cuts before year-end.

At the Federal Open Market Committee press conference in early August, Fed chair Jay Powell, signalled the Fed’s view that any boost to inflation from tariffs should only be temporary – and repeatedly stressed the risks in the labour market.

Though August’s weak Nonfarm Payrolls report shocked rates and the risk markets at the time, it did not prove to be a real game changer, and the positive “AI paradigm” narrative remains the most significant guiding force for stocks and risk more generally.

The outcome of the trade negotiations between China and the US, the world’s two biggest economies, has been postponed until later this year. Although Beijing’s economic power makes it a more difficult entity to be ‘bullied’ by rafts of sanctions, the country’s economy is still to emerge from its years-long relative – for China – economic malaise.

While Chinese policymakers battle to transition the economy from high investment to high (-quality) consumption, their efforts have been dogged by unfavourable demographics as well as swathes of corporate debt, most acutely accumulated by the beleaguered property sector. Producer price index (PPI) numbers in China are still in thrall to deflation and consumer data suggests that here, too, inflation remains very low.

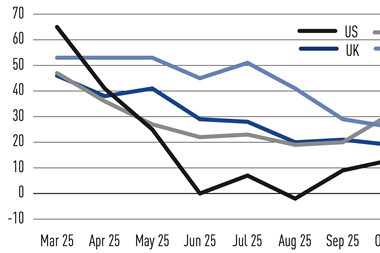

Bonds: yield curves steepen amid concerns over US employment

After his Jackson Hole speech in August, Powell repeated the Fed’s contention that policy could be eased even if inflation – boosted by tariffs – remains higher for many months, now that concerns about employment were ‘top of mind’. Despite September’s rate cut, there is less consensus on how rapidly subsequent cuts may happen.

Given job revisions – and the firing of the head of the BLS in August – analysing the next set of payroll numbers and ascertaining an accurate picture of the unemployment rate has become much harder, and not just for the Fed. Despite increased uncertainty surrounding the macroeconomic picture, as well as the unprecedented political pressure (and behind-the-scenes machinations) on both Powell and other Fed members, rates and risk markets seem to be pricing in a relatively benign outlook.

Though US curve steepening has happened, as seen across the developed world’s bond markets, more bearish forecasters suggest that it should be steeper yet and that possibly complacency is seeping in, given the fiscal outlook, ongoing tariff uncertainties, as well as ominous clouds building over the Fed’s independence credentials.

In Europe, another French government has fallen, again over contentious budget plans. Bund-OAT spreads have stayed near the wides reached during last summer’s political turbulence when first one then another government collapsed in the space of a few months. Thus, markets seem to be OK with current valuations given the ‘bad news’ already priced into OATs combined with an overlay of reasonably positive outlook for Europe risk generally.

There are tail risks, of course. If the political landscape in France continues to reveal a country wholly incapable of reining in its fiscal laxity, then further rating downgrades could become inevitable. And such political instability in France does Europe no favours, particularly with Russia emboldened by a lack of a concerted effort by the current US administration to rein in Moscow’s war against Ukraine.

Currencies: threats to Fed independence point to weaker US dollar

The conventional economic theory playbook for higher US trade tariffs, along with evidence from the first Trump administration, would argue for a stronger dollar. The argument runs that US consumers and businesses alike buy fewer imports, thus reducing demand for foreign currencies (so fewer sellers of USD), and that US tariffs tended to appreciate the US dollar, offsetting some of the tariff effects pushing import prices higher.

In addition to scrutinising the Fed’s move to cut its policy rate, and the direction of monetary policy, this year another wrinkle has appeared for the US currency – that of Fed independence.

The White House’s nomination of Stephen Miran to the Fed’s board of governors puts renewed focus on the administration’s currency interventionist stance. Months before his appointment, Miran notably proposed a “Mar-a-Lago Accord” to realign global trade and currency systems, and to broadly weaken the US currency while simultaneously preserving its reserve currency status.

Miran has also discussed the need for significant Fed/monetary policy reform, which critics have argued could result in giving the president much greater sway over both US monetary policy as well as the regulatory environment more generally.

With Miran’s appointment now confirmed by the Senate, we still await news on who is likely to take over from Powell when his term ends next year. Personnel changes at the Fed are keenly watched, as they have the capacity to unsettle market confidence as well as both strengthen or weaken the outlook for the US currency.